Class-conscious readers of this blog will have observed that many--no, nearly all--of our visits in the UK have concerned the upper-most one per cent--no, the upper-most one per cent of the upper-most one per cent--of the population, economically and historically. And so, in an effort to provide

balance, we visited Southwell's famous Workhouse, a trend-setter in early 19th century approaches to community care for the poor, the ill, the widowed, the orphaned, the unfit, and, yes, the lazy and the idle: the Takers.

But first, just a wee bit of background. The 1601 Poor Act provided that each parish would care for its needy, providing funds for a modicum of food, fuel, clothing, etc., enabling said needy to remain in their homes/hovels. This "outside" dole worked for a while. But by the early 1800s, things changed. Machines took away jobs; 200,000 troops returned from the Napoleonic Wars on the Continent; agriculture had its usual up and downs. The demand on parishes increased astronomically. But in Southwell and other places, they had an idea. Why not bring the dole "inside," creating workhouses where the poor could "earn" their keep, where idlers could be separated from the truly needy? The workhouses would be open to all, but upon entering, males would be segregated from females, husbands from wives, children from parents, and all made to work in redundant and unrewarding activities. (Is this what Marx called "alienation"?). The workhouse was to be necessarily unpleasant, thus encouraging people to become productive and to find (non-existent) jobs, and stand on their own feet. Oh, husbands and wives and children and parents could be reunited for an hour on Sunday afternoons. But no more "outside" dole.

Thus the Workhouse at Southwell and hundreds of other places in Britain. One tours this bleak place in the company of an audio-guide and dramatization wherein the agent of the local lord comes to see what is going on. Of course it is all appalling. Only in the last room of the Workhouse is there a display on the history of "welfare" in the UK that puts it all in some historical and political perspective. One should credit the National Trust for trying to tell this sad story at all. But the more recent context might have come earlier in the narrative.

As a WWII buff, I was always perplexed that the Brits unceremoniously dumped Churchill and his order even before all the dead of WWII were buried. It was about the conditions of the poor and the middle class in Britain, and opportunity. They had had enough. Fed up. For centuries. And they had earned better. The new Labour government enacted sweeping social reforms, providing benefits for maternity, unemployment, sickness, widows, and retirement. Great Britain has had free universal health care since 1948. The "outside" approach prevailed. The Workhouses are a monument to human suffering. And to greed and hard-heartedness.

|

| The Southwell Workhouse |

|

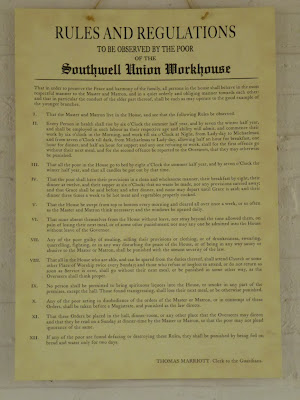

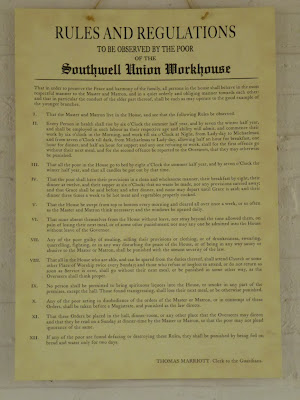

| Meaningful documentation throughout the Workhouse tour |

|

| Ditto |

|

| 4 oz of meat, three times a week |

|

| Our founder, the Reverend J. T. Becher |

|

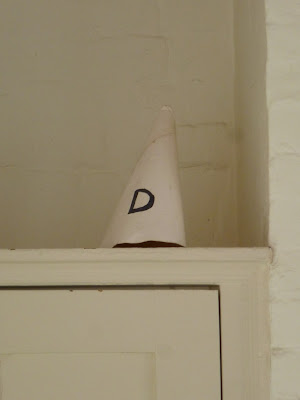

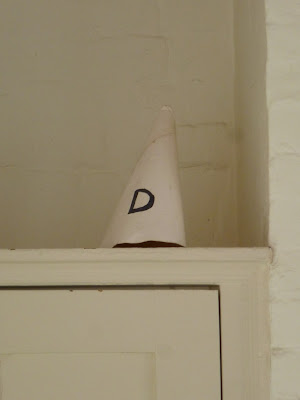

| In the children's classroom |

|

| Learning aid |

|

| Takers |

|

| Thought for the day, every day |

|

| Able-bodied mens' work-yard, latrines, and vegetable garden beyond |

|

| Dorm |